Table of Contents

Folk Regions

Three Ethnic Perspectives

Folk Music of the Florida Parishes

People of the Florida Parishes

In Retrospect

The Florida Parishes: An Overview

By Joel Gardner

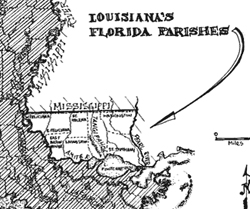

In colonial days, the area of Louisiana north of Lake Pontchartrain, east of the Mississippi River and Bayou Manchac, and south of the Mississippi border fell within the Spanish territory of West Florida. For a few months in 1810, before the United States annexed the land, it fell under the flag of the Republic of West Florida. Today, the region comprises eight parishes--East and West Feliciana, East Baton Rouge, Livingston, St. Helena, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, and Washington--and is known, in honor of its history, as the Florida Parishes.

In many ways, the Florida Parishes encapsulate the diversity of the state as a whole. Its residents are Scotch-Irish-English and Afro-American, French and Creole, Italian and Eastern European. Unlike the rest of South Louisiana, though, the Florida Parishes have seen very little creolization; rather, the traditions and ethnicity of its people have remained more discrete. The folk landscape of the parishes today includes plantation homes, piney woods, farmsteads, bayou fishing camps, Creole cottages, and Sunbelt subdivisions.

The major in-migration to the Florida Parishes was British-American in the 19th century: Tidewater English from Virginia and the Carolinas into the cotton plantations of the Felicianas; and Scotch-Irish, by way of the mid-South areas of Georgia and Mississippi into the piney woods of Washington, St. Helena, and Tangipahoa.

In front of the Anglo planters and farmers moved the Acolapissa, the major Native-American group of the pre-settlement era--now probably mixed with the Houmas in the Terrebonne Parish to the southwest--and the Choctaw, a few of whom remain along the bayous of the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain.

Behind the planters came the Afro Blacks, as slaves and later, when the post-bellum cotton economy dwindled, as sharecroppers. In the meantime, French, Spanish, and German settlers moved in from the south, to fish and hunt around the lake and rivers; and so did the freemen of color, the Black Creoles, who made homes in St. Tammany Parish, where they intermixed with the Europeans and the Indians.

The last to arrive, at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, were Italians, nearly all Sicilians, and Hungarians. Both formed communities, in Tangipahoa and Livingston parishes respectively, that remain cohesive today.

The extent to which all these ethnic groups have maintained and passed along customs from generation to generation has depended on the economic or social isolation chosen by or forced upon the group. Thus the Afro Blacks, restricted from integration into the social structure of the dominant class, maintain traditions of subsistence and sustenance, worship, and recreation that are characteristic of the deep South.

Food gathering and preparation (canning, smoking, cooking, etc.) are among the domestic folkways practiced by forebears that are still current and common among Blacks. Quilting is another one. For the older generation of Blacks today, quilting is an aesthetic and social activity, learned from parents and grandparents. By contrast, Anglo quilters have tended to adopt styles and patterns from craft books and national magazines rather than from oral tradition.

Not surprisingly, music plays a critical role for the Blacks of the Florida Parishes, from the gospel music sung in church every Sunday to the blues played at backyard barbecues and in clubs. Baton Rouge has recently resurfaced as a center of the blues; the home of such nationally known performers as the late Robert Pete Williams and Slim Harpo now boasts several active blues nightclubs and a style of playing that gives an urban edge to country roots. The annual River City Blues Festival, in April, features bluesmen such as Henry Gray, Silas Hogan, Guitar Kelley, and Tabby Thomas.

Like the Blacks, many of the piney woods Scotch-Irish retained an economic isolation from Sunbelt growth. In areas where logging once served as an industry and a way of life, many remain tied to the land, to small farms and traditional ways. Subsistence again provides the impetus; many maintain methods of food gathering and preparation as well as handcrafting of farm implements.

Traditional music of the piney woods whites is played at liquor-free clubs and festivals such as the Old South Jamboree and the Catfish Hayloft from Walker to Bogalusa, and gospel music is equally rich in many churches. Most recently, the Louisiana State Bluegrass Association under the leadership of Jim Nation and Kenny Lamb, sponsors monthly bluegrass shows in Denham Springs. Fiddling traditions remain, and some performers still use fiddlesticks and perform frolic and dance pieces such as "Sawyer Man" and "Pa Didn't Raise No Cotton and Corn."

Bayous along the Northshore jut out from the lake like so many fingers, and there the people and their customs have intertwined. French and German descendants alike fish and hunt, create the tools of their occupation, and produce goods from what they catch and gather. They are Quaves (from Cuevas), Maranges, and Glockners, and they have all adapted their heritage to their surroundings.

Lake Pontchartrain has always provided an abundance of seafood, and so fishing has played an important part in Northshore lifestyle. The implements of shrimping and crabbing are often handcrafted; even the tools used to stitch the nets are sometimes made by hand.

In Bayou Lacombe, just east of Mandeville, French, Creoles of Color, and Choctaws have intermixed. Their most striking tradition is the celebration of All Saints' Day, Toussaint, which includes lighting candles around each grave site in the cemeteries of Lacombe and blessing the dead. At these rituals, Creole-speaking worshipers gather with three or four generations of family to pay homage to their earliest French ancestors as well as their most recently departed.

The Sicilians of Tangipahoa and East Baton Rouge Parish also maintain a singular religious observance, that of St. Joseph's Day. The ancestors of most of the Italians in the Florida Parishes first worked the sugar fields across the Mississippi or the docks in New Orleans, then moved to the Hammond area and bought small strawberry farms.

The town of Independence was for years nearly all Sicilian; today, the population is somewhat more heterogeneous. Still, the town centers on its heritage with an Italian festival in April and St. Joseph's Day in March. The celebration offers gratitude to St. Joseph for the bounty of the earth and a share of that bounty to the community. Some families build home altars and invite their neighbors, while other worshipers construct an altar at the church and provide a meal for all to share. Following the showing of the altar, a procession honoring the Saint winds through town.

Despite the fact that a smaller percentage of Italian-Americans in Baton Rouge are of Sicilian origin, St. Joseph's Day is still their most important holiday. The Grandsons of Italy, a fraternal organization, build an altar that fills the wall of St. Anthony Catholic Church's gymnasium, and then they feed some 4,000 members of the community at large. At St. Jean Vianney Catholic Church nearby, the congregation invites retarded children and sufferers of Hansen's Disease as special guests.

About thirty miles southeast of Independence, the residents of Hungarian Settlement maintain the traditions of another European ethnic group. Foodways and performance dominate the Hungarian customs that have resisted assimilation. For example, cabbage rolls are ubiquitous at celebrations. Old Hungarian songs are sung and danced, and the traditional costumes are still made and passed on by men and women.

In the Florida Parishes today, as in the rest of Louisiana, many of the traditions practiced for centuries risk falling victim to the spread of the Sunbelt lifestyle. Revivalists learn their crafts from magazines and call themselves folk artists. Young people play rock 'n' roll instead of blues or bluegrass. Lake Pontchartrain, flooded with river water to protect low-lying New Orleans, each year loses more of its bounty of seafood. Still, an increasing awareness of cultural continuity, especially its link to environmental protection, should assure, in the Florida Parishes as elsewhere, the survival of the traditional ways of life.