Table of Contents

Folk Regions

Three Ethnic Perspectives

Folk Music of the Florida Parishes

People of the Florida Parishes

In Retrospect

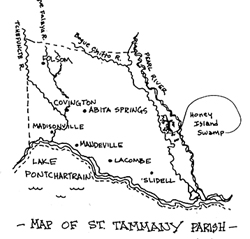

The Northshore—St. Tammany Parish

By Janice Dee Gilbert

Though both the north and south shores of Lake Pontchartrain were colonized by the same white groups--the French, English, and Spanish--the geography of the northern area, traditionally known as "the other side of the lake," insulated it against rapid, early development. Indeed, the distinct regional character was retained well into the mid-twentieth century.

During the exodus from the cities of the 1960s, the parish entered into a period of moderate growth, due mainly to an influx of New Orleanians. Still, the distinctive atmosphere of the Northshore was kept intact. Geography continued to protect the autonomy of the region as a whole. The first wave of urban flight took a course toward Slidell, the eastern tip of the parish, because of its easy access via I-10. The western and northern areas of the parish, connected to the city by the causeway, received only a trickle of immigrants. These were often older, retired people who had no need to commute to city jobs. More often than not, they had grown up in New Orleans and followed the tradition of summering on the Northshore. In a sense, these were not strangers to the area but seasonal residents who decided to settle in permanently.

After a brief "urban homesteader" movement in the 1970s, the migrational floodgates were opened. Disillusioned young urban professionals headed for the exclusivity and safety of new Northshore subdivisions. Joining the ranks of young families from New Orleans were corporate employees from the north. St. Tammany today, while not succumbing entirely to "bedroom community" status, is certainly commuter-oriented, attached to the financial nourishment of the city by two well-traveled umbilical cords, the Causeway and Slidell's five-mile bridge.

And the towns to the north, the last to be touched, are also feeling the change. Covington, long the seat of the parish's old money, still retains a vestige of Southern disdain for the nouveau riche. But the aggressive Toyotas and smug Mercedes, the sedate Chevrolets and even the sputtering pickups, are all speeding toward a homogenized society, in which the old ways are left by the wayside.

An encouraging and somewhat ironic feature of the cultural change in the parish is that the very newcomers who have changed the parish are also the most active in trying to save the old folkways. St. Tammany's historical society is guided in large part by new residents. Mandeville Horizons, founded a few years ago, seeks to unite natives and newcomers. The group sponsors cultural programs and stages a large native crafts festival each year. The Tree Alliance and other environmental groups are active in preserving the parish's natural beauty; for example, they recently passed a parish-wide tree ordinance. Planning and zoning commissions in the towns are taking an active part in historic districts, as is downtown Covington. Often the newcomers on such commissions are pitted against native residents who are opposed to preservation. The local politicians' rallying cry is always "Planned Progress," as they seek an optimistic middle line.

Historically, St. Tammany has always been a parish of newcomers. There is archeological evidence that prehistoric humans lived around Lake Pontchartrain 10,000 years ago. Paleo-Indian arrowheads have been found in the parish. These tribes were mainly hunter-gatherers. Since then, the lake has shaped and supported culture, first by providing food, then as a center for commerce. The indigenous crafts exist in St. Tammany today. Boat building, fishing, crabbing, net making, paddle making, and decoy carving are all related to life on the lake.

Indian groups included the Poverty Point group (1600 B.C.), the area's first pottery makers; the Tchefuncta tribe (600 B.C.-400 A.D.); the Marksville (200 A.D.-400 A.D.); the Troyville (400 A.D.-900 A.D.); the Coles Creek culture (700-1300 A.D.); and the Plaquemine-Historic bank (1200-1700 A.D.). White settlement began in 1699, when Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville, was exploring the Mississippi in a canoe. A shortcut to the gulf recommended by his Indian guide led him through Lake Maurepas and Pass Manchac. About sunset on March 27, he entered the lake, which he christened Pontchartrain, after the Count de Pontchartrain, France's minister of finance under Louis XIV. He disembarked at Goose Point, near what is now Lacombe, thereby becoming the first white tourist to set foot in St. Tammany. He found the mosquitos intolerable, the land too marshy, and dismissed the area as totally unfit for settlement.

The Acolapissa tribe did not agree. In 1702, they migrated from Bay St. Louis to Bayou Castine, near Mandeville, in search of plentiful food and religious freedom from white Christian zealots. There is documentation of trade between the Acolapissa tribe and the New Orleans settlers as early as 1725, thus beginning the lucrative regional commerce which sustains the area to this day.

Other tribes that sporadically inhabited the areas included the Biloxi and the Pensacola. It was the Choctaw, however, who populated the area after widespread white colonization. Choctaw basketry, kept alive by a handful of craftspeople through the years, is an enduring native craft. The Choctaws appear to have been nomadic, following hunting and fishing seasons parish-wide. Older parish residents still recall the Choctaws, who sold their baskets, gumbo filé, and other herbs along the roadways of St. Tammany. Mrs. Germaine Cousin Smith, lifelong resident, recalls how the small band of Indians used to sleep on the porch of her grandmother's lakefront home, waiting to board an early morning steamer to New Orleans, where they sold their wares at the French Market. "They'd walk all the way from Bayou Lacombe, file noiselessly onto the porch, and leave before daybreak. On the way back, the Indians would again break their long trip on my grandmother's porch. She was a great friend to the Indians," Mrs. Smith notes with pride.

By 1748, the settlement of Lacombe had been established on Bayou Lacombe (named after an early resident) and was a known refuge for runaway slaves.

By the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Chiconcte (Madisonville) and Barrio of Buck Falia (Covington) had begun to develop as trade and transportation centers. The Port of Bayou St. John in New Orleans began trade excursions across Pontchartrain to the settlements, and vessels began to be built on the Northshore. So began an industry in Madisonville which continues today.

In 1810, President James Madison claimed Spain's West Florida territory to be part of Louisiana and Governor Claiborne established boundaries of the parish, naming it St. Tammany, probably after Tamanend, a Delaware Indian chief.

After a boom before the Civil War and a slump during Reconstruction, business revived around 1880. The vast pine woods, left intact until this time, began to fall to lumber companies. Tourist trade also resumed, with six steamers making excursions twice a week.

Though St. Tammany was always rural, farming was a dominant economic force. The lumber business with attendant industries of pine tar, turpentine, and pitch provided stability with the advent of the railroads. It also denuded the landscape, eradicating thousands of acres of virgin pine and cypress. Sheep farmers and cattle ranchers took advantage of the resultant pasture land. Brickyards made use of local clay. Residents in subdivisions between Mandeville and Covington occasionally still find piles of old bricks in their yards. The shipbuilding industry, though suffering periodic reversals, is still viable. And, of course, the lake provided trade and tourism. However, with the Depression came the end of St. Tammany's grand tourist era.

The result of the type of industry which tended to draw people from other areas, be they skilled laborers or tourists, was a constant stream of new blood. In addition to the old lines of Spanish and French settlers, later years saw Irish, German, and Italian immigrants drawn to the area in search of employment. The genesis of St. Tammany as a bedroom community for New Orleans came in the l950s, with growth primarily concentrated in Slidell. The proximity to the Michoud/NASA space aeronautics plant in Eastern New Orleans brought white-collar workers from the North. Suburban growth began to spread to the west in the late seventies, and it continues at a rapid pace. Not only do the newcomers have different cultural backgrounds, but their financial status is disparate with the established community as well. This fact further expands the cultural milieu.

In some ways, Covington is much further removed from Slidell than the miles would indicate. It is still a town of old families; its old homes were passed down from generation to generation. Slidell seems to have long since forgotten its roots and is now a bustling commercial center, its residents abiding in the sprawling suburbs. Madisonville's small, working-class community is likewise far removed from the burgeoning artist's enclave of Abita Springs, having more in common with the equally untouched community of Lacombe. And Mandeville seems to have a foot in both past and present worlds. The old lakefront mansions and Victorian summer houses are now being restored by young families, but just as many people opt for the more contemporary ambience of the new suburbs.

It is the very presence of growth and diversity, however, which prompts many of its citizens--from the native clinging to the security of the old ways to the newcomer wanting to put down cultural roots--to revere the old crafts and customs.

The Black community, perhaps the only distinct ethnic group in the parish, is small. Blacks fleeing slavery crossed the lake from New Orleans to the Lacombe area, which has the most influential Black presence. Over the years, Blacks intermingled with Indian, Spanish, and French to create an interesting racial mix. Many of these interracial people "passed" years back, preferring to claim their dominant ancestry as white. Today, residents cannot be judged Black or white by appearance. French and Spanish surnames cross racial lines, a situation that is also true in the area just north of Abita Springs, which was also once home to Indian tribes.

I have interviewed people who called themselves Black, who wished to deny, or at least downplay, their Indian blood. When I asked one influential member of the community in Lacombe the reason for this, he told me that these days a Black who claimed Indian heritage would be chastised for trying to deny his race.

The Black community in Mandeville is clustered in two small areas. Unlike Lacombe, the community is a poor one, carrying little political clout. The situation is much the same in Covington and Madisonville.

Slidell, perhaps because of size, mobility, or the influx of many northern workers, has a good representation of Black people in community government and businesses, though certainly not to the extent of its neighbor, eastern New Orleans.

There has been, however, a Black-owned community center in Mandeville for generations. The Dew Drop Social and Benevolent No. 2 was founded May 5, 1885 by Olivia Eunio. The wood frame hall on Lamarque Street was erected on January 1, 1895. Older community members recall Louis Armstrong performing there in his early days. The building has been used as a meeting place for the Masons and the Holiness Church. Mrs. Celeste T. Lee, now in her nineties, was once owner of the building.

Also in Mandeville, on Marigny Street, are two brothers of Black and Indian heritage. Leon Laurent, in his nineties, lives in an old house surrounded by a primitive, hand-sawn cypress fence of the type usually only found in the bayou country to the south. He still grows a huge garden each year. One of his crafts, a wooden bird trap, is displayed in The Creole State: An Exhibit of Louisiana Folklife located in the State Capitol and online.

Bibliography and Archival Resources

Cashio, Cocran, Inc. St. Tammany Parish: Open Space and Recreation, Interim Sketch Plan. New Orleans: Regional Planning Commission for Jefferson, Orleans, St. Bernard and St. Tammany Parishes, 1973.

____. Selection and Analysis of Historic, Archeological, and Scenic Areas, St. Tammany Parish. New Orleans: Regional Planning Commission for Jefferson, Orleans, St. Bernard and St. Tammany Parishes, 1973.

Chamber of Commerce, Mandeville. Historical Survey, Mandeville, La. Mandeville: Chamber of Commerce, 1973.

Ellis, Frederick S. St. Tammany Parish. Baton Rouge: Pelican Publishing Co., 1981.

Fischer, Millie. This Was Our Town--Mandeville. Mandeville: The Mandeville Bantum.

Jahnke, Carol Saunders. Mr. Kentzel's Covington, 1878-1890. Baton Rouge: Legacy Publishing Co., 1979.

League of Women Voters. Parish of St. Tammany: A Citizens' Guide. Covington: The League of Women Voters, 1981.

Regional Planning Commission for Jefferson, Orleans, St. Bernard and St. Tammany Parishes. St. Tammany Parish: Report on Land Use. New Orleans: The Regional Planning Commission, 1976.

Roberts, W. Adolphe. Lake Pontchartrain. New York: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1946.

St. Tammany Parish, Department of Development. Existing Land Use Study, Covington, Louisiana. Covington: The Department of Development, 1981.

St. Tammany Parish Planning Commission. Existing Land Use Study for Abita Springs, Louisiana. Covington: The Parish Planning Commission, 1979.

Schwartz, Adrian D. Sesquicentennial in St. Tammany. Covington: Covington City Council, 1963.