Introduction to Delta Pieces: Northeast Louisiana Folklife

Map: Cultural Micro-Regions of the Delta, Northeast Louisiana

The Louisiana Delta: Land of Rivers

Ethnic Groups

Working in the Delta

Homemaking in the Delta

Worshiping in the Delta

Making Music in the Delta

Playing in the Delta

Telling Stories in the Delta

Delta Archival Materials

Bibliography

The Fabric of Family: Preserving the Parker Family's Quilting Heritage

By Kerry Davis

Many times families have heirlooms that are passed down through generations, connecting the present to the future and the past. Quilts are just such treasured heirlooms, but of equal importance is the accompanying heritage of quilting, also passed from generation to generation. One Jonesville, Louisiana family, the Parkers, has a quilting heritage spanning at least five generations. For the Parkers, even though the heritage of quilting did not move linearly from one generation to the next, each generation did eventually embrace this old tradition. The women of this family are Alice, Virgie, Wanda, Camillia, and Katrina. Alice taught her daughter, Virgie, to quilt. The tradition skipped a generation when Virgie taught her grandson's wife, Camillia to quilt, and then it moved back a generation when Virgie and Camillia taught Wanda (Virgie's daughter-in-law and Camillia's mother-in-law) to quilt. Finally, the Parker matriarchs taught quilting to Camillia's daughter, Katrina, who went on to get university degrees in fine art. Despite a recent tragedy that destroyed some of the Parker family quilts, the heritage of quilting still unites these women. Their quilting experience ranges from traditional quilting learned informally at the knee of relatives and done for necessity and pleasure, to revivalist techniques drawing from popular quilting books, and finally to fine art incorporating the quilting tradition.

Growing up in a large farming family in the middle of the Louisiana Delta, Camillia Tolbert Parker was exposed to sewing at an early age. Although her mother, Violet Tolbert, never quilted, she made clothing for her husband, Riley, and their nine children. Violet also taught her daughters to sew, and by the time they were teenagers, they were helping make clothes for the rest of their siblings. Two of Camillia's older sisters, Shirley and Earlene, became seamstresses after they were married. Earlene became a designer as well, focusing on making specialty pageant dresses for beauty contestants and specialized winter gear for hunters. She even patented some of her pattern designs. Like her sisters, Camillia became proficient at making clothes, yet she recalls that even as she began to sew, she was always more interested in the fabrics she was using than in the clothes she was making. She even admits that she would be attracted to a fabric of a particular print or color and buy it without really planning on making a garment out of it.

Camillia was first exposed to the art of quilting when she married Ricky Parker, from Jonesville, Louisiana. Ricky's paternal grandmother, Virgie Parker, was a traditional quilter who had learned to quilt from her mother, Alice Poole. Although the family is not certain where Alice learned to quilt, she was also a traditional quilter. Even though Camillia soon fell in love with the quilts of her new family, she did not consider learning the craft until she became pregnant, and Virgie began making her a baby quilt. When Camillia expressed an interest in quilting, Virgie was more than happy to answer her initial questions, eventually guiding her first attempts at quilting. With Virgie's assistance, Camillia pieced a top for a baby quilt, which Virgie then quilted for her (Figure 1). Both women quickly discovered that Camillia had an affinity for the art, served by her early exposure to sewing and her love of fabrics. Also, she had time for serious quilting, since her husband, Ricky, worked on an off-shore drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico and was frequently away from home for weeks at a time. Her desire to learn everything she could about quilting drove her to the library when Virgie could not answer her questions. Since the quilting revival had made quilting popular, Camillia found many books on the subject. Many times she would carry a book to Virgie and ask her to explain some technique that she could not quite master from the written explanations. She learned most of her traditional piecing and quilting techniques from Virgie and most of her appliqué skills from quilt revival books.

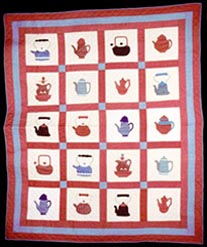

Initially, Camillia was a cautious quilter. After learning to piece by hand and do machine appliqué, she recalls when she first decided to try hand-stitched appliqué. She wanted to make a "Rose of Sharon" pattern, but she first made a three-block wall hanging before making a full-sized spread (Figure 2). She explains her hesitation: "Much more time could have been wasted making a full-sized quilt" if she had not enjoyed the experience. That first cautious foray into hand quilting affirmed her love of quilting, and she not only completed her "Rose of Sharon" quilt, but went on to make many others (Figure 3). Some of them won quilting awards, such as her "Teapot" quilt, which won Best in Show in the 1993 Jonesville Soybean Festival Quilting Contest (Figure 4). Camillia admits that time is an important part of quilting for her. She says that a fancy, heirloom quilt can take her anywhere from a year to two years to make. She believes that time is part of what makes a quilt special. She laughingly explains that she does not like to waste too much time on quilts she intends to use. Her plainer, everyday quilts usually take between two weeks to a month to complete.

After Camillia became proficient at quilting and was making her own quilts, another member of the Parker family expressed an interest in learning the craft--Ricky's mother, Wanda Parker. While she had always loved her mother-in-law's quilts, she had never felt inspired to learn how to quilt until she saw Camillia quilting. She says she realized that she could learn just like Camillia had learned. Virgie and Camillia began to teach Wanda what they knew, and soon they were all three quilting together. They typically used a frame on a stand for their quilting. Sometimes, one of the women would piece a quilt and then they would all quilt it together. Other times, they would all three work on both piecing and quilting.

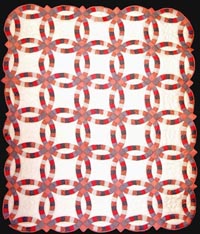

Wanda says her "most favorite" quilt is a "Double Wedding Ring" pattern, which Camillia pieced and gave to Wanda, who then quilted it (Figure 5). They definitely influence each other's quilting. For example, Camillia loves to create her own appliqué patterns or adapt existing ones. One of her favorite appliqués is an original gnome quilt inspired by a book about gnomes (Figure 6). Wanda was inspired by Camillia's original designs so much that she decided to create her own pattern for a Christmas appliqué quilt (Figure 7).

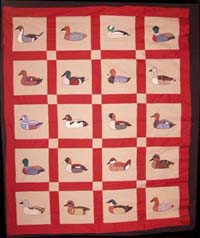

Camillia's quilts have continuity according to her taste in fabrics and color. Her earlier quilts to her most recent quilts show similar choices in quilt patterns and fabric color and coordination. Her favorite colors are pastels, and like most revivalist quilters, her favorite material is cotton. During an interview in 2003 when asked about her favorite colors, she replied, "I don't like to look at dark colors." Gesturing to several of her favorite quilts in pastel colors, she explained, "This is how I see color. These are true colors. They are beautiful." While most of the heirloom or special quilts Camillia makes are pastel, some of her "plain" quilts use richer colors, like the brown "Log Cabin" quilt that she says has been on her bed for the last fifteen years (Figure 8), or the brick red "Duck" quilt that was one of her first machine appliqué quilts (Figure 9. Whatever the color value of her quilts, rarely does Camillia use contrasting colors. Sometimes, however, she will incorporate what she calls "a difference" or "something different" into a quilt.

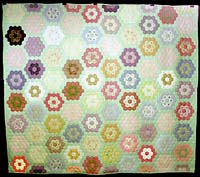

One example of a quilt containing a difference is a "Grandmother's Flower Garden" that the Parker women made together for Katrina (Figure 10). Quilted with pale lilacs, yellows, pinks, and greens, the quilt blocks blend softly together, with one exception. One of the flower blocks, made of dark brown fabrics, is jarring in the field of pastel blocks, which, as Wanda said, is the point. Camillia wanted to include the dark brown flower for the very reason that it seemed to mar the quilt. That brown block is a message to Katrina that nothing is perfect, that flaws are part of being human, but they are no reason to give up on trying to be a better person. Another quilt that displays Camillia's ideas of "a difference" is a "Star" quilt that is also done in soft pastels (Figure 11). Two points on one of the stars, however, are distinctive because of their high contrast material. Camillia explained that the high-contrast material was impossible to ignore, and since that material came from Katrina's baby clothes, those two star points would always "startle" her and remind her of her baby daughter.

Wanda, Camillia, and Virgie Parker have made many quilts together which they consider priceless heirlooms because they span generations. Particularly special to them are the quilts that were begun by Virgie's mother, Alice, who years before had started piecing several tops which she never finished (Figure 12).

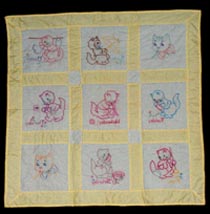

Wanda and Camillia found the unfinished tops and decided to finish piecing and quilting them to give to their grandchildren. They are always trying to get as many family members as possible involved in any stage of their quilting. One way they do this is by inviting non-quilters to design appliqué patterns for them. For example, Wanda's nephew, Robin Stone, a professor of fine art, made Wanda a large painting of tulips. To continue this theme, the women asked Robin to design a tulip appliqué pattern, which they then pieced and quilted (Figure 13). When Camillia decided to appliqué a memory quilt for Katrina, she invited me, her niece, to design a block representing one aspect of Katrina's college years. Since I am Katrina's first cousin and had been her roommate through most of her college years in art school, I designed a paint brush and palette pattern for my block. Katrina also designed patterns for this quilt and for others. Katrina also quilts with her mother and grandmothers, as she did when making the "Grandmother's Flower Garden" with the brown flower. She became the fourth generation of Parker women to contribute to this quilt's construction (Figure 10). Katrina herself learned to quilt by watching her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother as they quilted together. She made her first quilt, "Kittens" when she was 9 years old with the help of her mother (Figure 14).

Katrina has gone on to embrace her family's sewing heritage, although in a less traditional way. Receiving both her B.F.A. and M.F.A. in art from Louisiana Tech University, Katrina explored drawing and painting in the classroom setting. However, she found that, like her mother and grandmothers, she had an affinity for fabric and sewing, an affinity that eventually found its way into her graduate work in art. Like her Aunt Earlene, Camillia's sister, Katrina began designing her own original patterns for purses and clothing, most notably, coats. At first, she united her formal education with her family's sewing traditions by including pieces of dress patterns in her collages (Figure 15). Hesitant at first to display her sewing designs in her art classes, she eventually did show them, and was met with positive reviews. She first presented a small pieced quilt of peach and blue strips and squares as an abstract composition. Her most popular design, however, was a camouflage evening coat replete with a ballroom train, puff sleeves, and a sumptuous pink silk lining (Figure 16). She is currently working on a new quilt that will have a top and lining of translucent chiffon, and the batting will be strands of hair collected from every female family member in both the Parker and the Tolbert families. When not creating her own fiber art, Katrina still quilts with her mother and grandmother.

For the women of the Parker family, quilting is more than a pastime or hobby. As Camillia said, "These quilts are who I am." The Parker family quilters see quilts as a way of preserving memories, of providing lessons, and of conveying love. They are a way of connecting to future Parker generations. Virgie made each of her three grandsons an heirloom quilt with traditional patterns, and Wanda also made quilts for her grandchildren. Camillia went a step further, and not only made quilts for Katrina, but she made quilts for Katrina's future children, grandbabies yet to be born. Many of these quilts have never even been spread over a bed before being lovingly wrapped and stored in an armoire. She says, "Those quilts are heirlooms. They are Katrina's inheritance."

One and a half years after the Parker family quilt documentation and interview, Ricky and Camillia's house burned, along with all its contents and their two dogs. All of her quilts (except for baby quilts she had made for her extended family) were destroyed, as well as Katrina's separate art studio containing most of her art, quilting, and sewing from the past 15 years. Camillia and Katrina were devastated and heart-broken by their loss. When trying to explain what she was feeling about the loss of her quilts the day after the fire, Camillia spread her hands out with the palms up and said, "They're time and youth I can't get back. My eyes aren't good enough, and my body isn't strong enough to replace those quilts." In particular, she mourns the quilt containing Katrina's baby clothes (Figure 11), and another quilt she had not yet finished. She says she had been working on a quilt that would have been her "masterpiece," another "Grandmother's Flower Garden" pattern (Figure 17). Each scrap of fabric in it had been no larger than one inch. She had started piecing it after having surgery and realizing that she might not always have the ability to do such fine work. She says, "I planned for getting older, but I didn't plan for this."

Katrina also mourns for the quilts and other art that burned, but she says, "Not everything is lost." The inheritance is gone, but not the heritage. She admits that what was lost was irreplaceable, yet she has the time and knowledge to make more quilts. Katrina also added about the quilts, "They have been preserved, in a way." She realizes that, because most of the quilts were documented by the Louisiana Quilt Documentation Project, the family still has access to photographs and information on each quilt. Although future generations of the Parker family will never own these quilts, they will be able to learn about them and know their quilting heritage.